THIN SPACES, DEEP TIME: ART, TECHNOLOGY, AND A CHANGING WORLD IN 2025

Christopher Roantree & Akarsh Kummattummal

WCPF Creative DIRECtor, lizzie glendinning, meets artists Chris roantree & akarsh kummattummal to discuss their creative partnership and how their work navigates art in an interconnected, disrupted age.

INTRODUCTION BY CHRIS ROANTREE

People often ask how we collaborate on a single artwork at the same time. In 2025, I find this question interesting myself—technologies have been disrupting the art scene for centuries, and collaboration is just one piece of that evolving puzzle. Post-World War II marked some of the most controversial disruptions to the visual experience. During that golden age of American capitalism, industrial manufacturing gave rise to consumer spending and a mass surge in suburbanisation, its clear to see how a Fine art of that time seemingly celebrated this, but perhaps was also staging a rather deceptive protest or a warning perhaps.

J.G. Ballard’s Kingdom Come (2006) captures this tension perfectly:

“The suburbs dream of violence. Asleep in their drowsy villas, sheltered by benevolent shopping malls, they wait patiently for the nightmares that will wake them into a more passionate world.”

Ballard evokes the downstream horror of a hyper-capitalist society. Celebration or protest that was half a century ago and common supermarket products, comic books, newspaper headlines, movie icons were elevated to the pedestal of Fine Art. The traditional studio morphed into an industrial factory, with print becoming the primary vehicle for expression. Political decisions driving war required economic stimulus, giving rise to a more financialized art scene. Cheap spaces in booming economies became playgrounds for artists—think London in the ‘90s. But today, the downstream effects of poor financial regulations and fiscal policy over the past 25 years have created walled gardens around capital, stifling the next generation of creatives.

Lizzie glendinning | how do you see The Plight of Young Artists Today?

CR | Artists are resourceful, but they have limits. In 2025, today young creatives can hardly even find a space to work in let alone have enough financial freedom to distill the events of this exponential world into some form of visual response. And the world is changing rapidly where perhaps we are approaching a technological singularity where on a societal level we transform quite unpredictably and profoundly so. I recently listened to a talk on AI predicting an unprecedented level of productivity: the equivalent of every person on Earth having PhD-level intelligence, working 24/7, soon to be integrated into a robotic infrastructure. Where do artists—and print—fit into this future?

I believe hubs, print rooms, studios, collectives, and art fairs are vital. They’re not just survival mechanisms—they’re spaces where artists can thrive and network with galleries. Affordable prints lower the barrier for new collectors to enter the market, explore idiosyncratic tastes, and diversify their holdings across styles and domains. Dedicated studios, fairs, and galleries become accessible gateways to London’s cream of creative talent. It’s a way to keep art alive amid technological and economic upheaval.

LG | HOW DID YOur Collaboration EVOLVE?

AK | It’s rooted in a shared interest in the materiality of paper and print, but also in our personal visual histories—narratives shaped by popular culture and an interconnected world. Though we grew up thousands of miles apart, cinema and gaming have left their mark on us both. When we produce a series of works, it’s like making a film: no script, a single camera, and a very very low budget. How do we celebrate and react to our vast library of influences and questions that surround our ever changing work —delivering them to an audience—through still images that tell a story and build an escapist world even?

CR | We turned to the landscape genre but sought to disrupt it. An inspiring moment came at a British Museum conference tied to the Silk Roads exhibition. Professor Simon Kaner from the Centre for Japanese Studies discussed “Thin Spaces, Deep Time,” a term coined by a colleague to describe landscapes of spiritual significance. The Helgo Buddha—a 6th or 7th-century artifact from the Swat Valley, found in 1956 on a Swedish island 3,000 miles away—embodies this idea. Its journey along overlapping trade routes mirrors an interconnected world where sacred objects travel far from home, landing in unexpected places like an island on an lake in the Scandinavian mud.

LG | How has working together influenced your personal practice? Has it changed your approach or technical abilities?

CR | We’ve learned a lot from each other. We share a lot of influences—cinema, pop culture, gaming, and comics. Our process is like being in a band—syncing up rather than competing.

We work side by side most of the time, but sometimes we split tasks. I might handle aquatint or wax grounds while Akarsh works on watercolor studies. Other times, I focus on detailed pencil drawings while he manages digital files. But when we’re in our ‘sweet spot,’ we’re together—laying down ink, painting onto aquatints, making marks in acid. That’s where we find the most enjoyment.

AM: It is always evolving. We adapt and grow

LG | Has printmaking’s constant innovation and new technologies influenced your collaboration?

CR | It’s interesting because printmaking has always evolved, but technology wasn’t why we started collaborating—we just wanted to work together. Our priority is staying visually sensitive to traditional etching.

Some assume working with polymer plates means we’ve abandoned traditional drawing skills, but that’s not the case. Norman Aykroyd invited me to teach etching at City & Guilds after I graduated from the Royal College of Art, where I spent all my time etching metal plates. I still teach etching because I love it.

Photopolymer lets us seamlessly combine our marks, but it’s actually more expensive and time-consuming than traditional etching. We scan metal etchings, overlay them, and transfer them onto photopolymer plates—all while maintaining mark integrity. Some stigmatize photopolymer, but it’s still etching, just with water instead of acid. We ignore skepticism and focus on pushing landscape art forward with influences from film and gaming.

LG | I’d love to hear about the influence of gaming and geopolitics on your work

CR | That’s a cool question—gaming and geopolitics!

In an art gallery, you escape into an image; in gaming, you escape into an interactive world. Many game designers are classically trained artists, and there’s a lot of synergy between gaming and fine art. Akarsh has even helped create games, so he can speak more to that.

AM | Yes. The way games build immersive worlds is something we think about in our work. They create layers of reality, and we try to achieve a similar effect through printmaking.

CR | Exactly. We want to disrupt traditional landscape art, infusing it with contemporary cultural references—whether gaming, cinema, or politics. It’s about engaging audiences while staying connected to historical techniques.

LG | WHERE DID THE CONCEPT OF Thin Spaces, Deep Time COME FROM?

CR | “Thin Spaces” has Celtic roots, describing places where the boundary between the earthly and divine feels permeable. “Deep Time,” popularized by John McPhee in “Basin and Range”, humbles us with the universe’s vast timeline, dwarfing human existence. In our lifetimes, we’ve seen environmental shifts that echo the climatic visions of cinema over the past 30 years—disaster movies and fantasy epics where CGI replaced models and the monster really looked like it was levelling the city. After 9/11, the disaster was very real, and urban spaces became Thin Spaces.

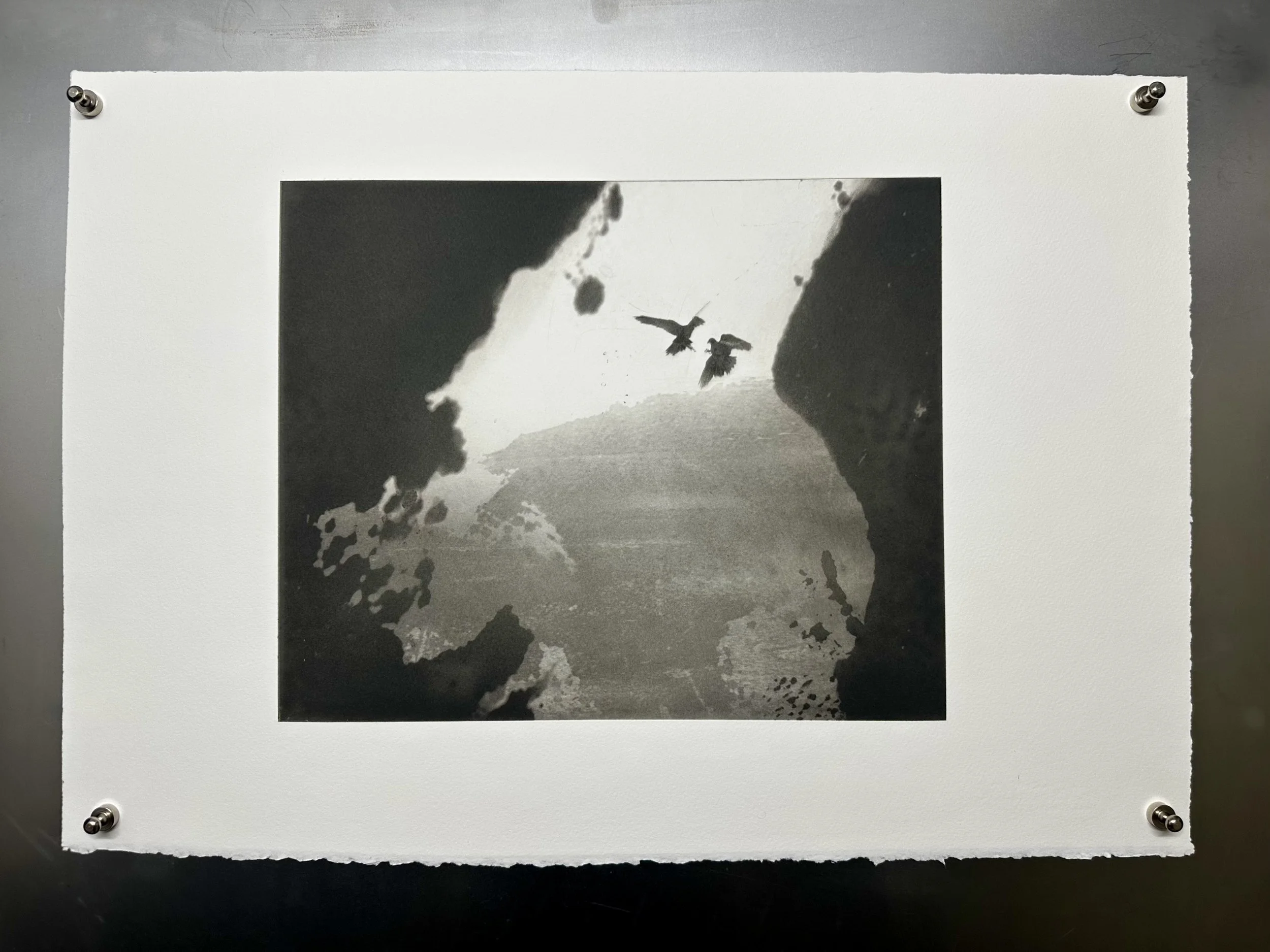

AK | In our current series, Thin Spaces, Deep Time, we disrupt the landscape genre further. We explore spaces as shelters, sites of worship, and protections against a transformative, dangerous environment. Recurring motifs like the statue and the wolf serve as metaphors for obsolescence and the call for a much wilder world. Our aim is to create beautiful work that carves a unique place within the landscape tradition while drawing on the richness of our shared cultural history and the volatility of today’s world.

LG | HOW DO YOU SEE Art’s Role AS TransformatiVE?

CR | Artists have long responded to societal shifts—economic, geopolitical, technological—elevating them onto the pedestal of Fine Art. From post-war consumerism to today’s tech-driven singularity, they’ve adapted. Right now, the most critical spaces are the platforms where talented, resourceful artists can speak. Hubs, studios, and fairs aren’t just infrastructure—they’re lifelines. They ensure art doesn’t just survive but thrives, offering collectors and creators alike a way to navigate this unpredictable era.As we work together in 2025, we’re not just making art—we’re building worlds, reflecting change, and asking where we fit in the deep time and thin spaces of tomorrow.

YOU CAN VIEW AVAILABLE WORKS BY ROANTREE X KUMMATTUMMAL IN OUR CURRENT INTAGLIO PRINT DROP HERE